- Home

- Lydia Kang

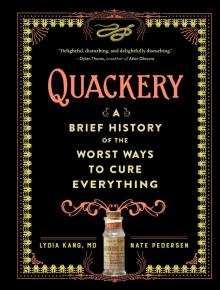

Quackery

Quackery Read online

Quackery

• A •

Brief History

of the

Worst Ways

to Cure

Everything

Lydia Kang, Md

Nate Pedersen

Workman Publishing • New York

•• Dedication ••

This one is for April for clearing the way.

—NP

To my father and brother, two of the best and most un-quacky physicians I know. And to my mother, whose love can heal just about anythin.

—LK

Contents

Introduction

Elements

Prescriptions from the Periodic Table

Mercury

Antimony

Arsenic

Gold

Radium & Radon

The Women’s Health Hall of Shame

Plants & Soil

Nature’s Gifts

Opiates

Strychnine

Tobacco

Cocaine

Alcohol

Earth

The Antidotes Hall of Shame

Tools

Slicing, Dicing, Dousing, and Draining

Bloodletting

Lobotomy

Cautery & Blistering

Enemas & Clysters

Hydropathy & the Cold Water Cure

Surgery

Anesthesia

The Men’s Health Hall of Shame

Animals

Creepy Crawlies, Corpses, and the Healing Power of the Human Body

Leeches

Cannibalism & Corpse Medicine

Animal-Derived Medicines

Sex

Fasting

The Weight Loss Hall of Shame

Mysterious Powers

Waves, Rays, and Curious Airs

Electricity

Animal Magnetism

Light

Radionics

The King’s Touch

The Eye Care Hall of Shame

The Cancer Cure Hall of Shame

Acknowledgments

Credits

About the Authors

For shocks and giggles: a Russian electric shower.

Introduction

Humbug. Charlatan. Quack. Con artist. Swindler. Trickster.

For a long time, words like these were used to describe those who preyed on our fear of death and sickness by peddling wares that didn’t work, or hurt us, or sometimes killed us.

But quackery isn’t always about pure deception. Though the term is usually defined as the practice and promotion of intentionally fraudulent medical treatments, it also includes situations when people are touting what they truly believe works. Perhaps they’re ignoring—or challenging—scientific fact. Or perhaps they lived centuries ago, before the scientific method entered civilization’s consciousness. Through a modern-day lens, these treatments can seem absolutely absurd. Weasel nuts as a contraceptive? Bloodletting to help cure blood loss? Burning hot irons to fix the lovelorn? Yep.

But behind every misguided treatment—from Ottomans eating clay to keep the plague away to Victorian gents sitting in a mercury steam room for their syphilis to epilepsy sufferers sipping gladiator blood in ancient Rome—is the incredible power of the human desire to live. And this drive is downright inspiring: We are willing to ingest cadavers, subject ourselves to boiling oil, and endure experimental treatments involving way too many leeches, all in the name of survival.

This drive also leads to incredible innovation. After a long battle to achieve lower death rates (and reduce screaming), doctors now perform surgery when we’re blissfully anesthetized. As an added bonus, their hands aren’t dripping with pus from the prior surgery case. We can fight cancer on a molecular level, in ways our ancestors never dreamed. Diseases like syphilis and smallpox are no longer an enormous burden on society. It’s easy to forget that along the way to this progress, innovators were scoffed at and shamed; patients suffered through their doctors’ mistakes, and sometimes even died. None of today’s medical achievements would have occurred without challenging the status quo.

But there is, of course, a dark side. That desire to heal and live longer is about as addictive as opium itself. Scientists, impersonating Icarus, try to best one another in making drugs more effective and more potent. Emperors send their alchemists on ridiculous quests to unlock immortality. Charlatans decide that you need a new pair of implanted goat testicles. Sometimes, we’re so desperate for a cure, we’ll reach for anything.

Even radioactive suppositories.

Let’s be honest. Being healthy isn’t enough for many of us. We want more—eternal youth, perfect beauty, boundless energy, the virility of Zeus. And herein the quack truly thrives. This is where we start to believe that arsenic wafers will give us that peaches-and-cream complexion and that elusive gold elixirs will fix broken hearts. Hindsight makes it easy to laugh at many of the treatments in this book, but no doubt Dr. Google has assisted you in searching for a simple cure to a pesky problem. None of us are immune to wanting a quick fix. A hundred years ago, you might have been the person buying that strychnine tonic!

Clearly, we needed to be saved from quacks—and from ourselves. The rise of patent medicines in the nineteenth century drove America to its turning point. With the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the United States cracked down on false and misleading labels, unsafe ingredients in food, and the adulteration of medical and food products. In 1930, the watchdog bureau became known as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Later laws in 1938 covered medical devices and cosmetics, and a 1962 law added scientific rigor to the drug industry.

Did regulations cure America of its quackery? Of course not. Despite modern scientific breakthroughs, the FDA, and a pretty damn good understanding of how the human body works, quackery’s tentacles still touch almost every aspect of the healthcare and cosmetics industry. This is why you’ll read a present-day update in many of our chapters. In a surprising twist, some quack cures, like leeches, have transformed into real, working treatments. But in many cases (like eating tapeworms for weight loss), quackery simply lingers on and on … and on.

To continue battling charlatans, we need a more complete understanding of how the human body functions and how disease works. We also need to keep open minds about ways to combat disease and improve longevity. Finally, we need to keep our guard up. There will always be quacks out there ready to take full advantage of human desperation before science and medicine can find solid solutions.

So how does one become a wary, discerning consumer with an open mind? Beware that quack medicine often relies on anecdotal evidence, or the endorsement of a celebrity physician, to convince us something works. Also, look deeper into claims made that “studies show XYZ is amazing.” These “studies” should have been rigorously performed, peer-reviewed, and repeatedly tested by various entities to show effectiveness. And they rarely are. Our own biases—confirmation bias, ingroup bias, postpurchase rationalization, and a host of others—all have heady effects on our ability to systematically evaluate treatments as varied as herbal cough drops, electronic cancer zappers, or pricey plasma-injected facials.

In the end, it comes down to a few simple questions. Do you believe there’s solid evidence that it’s going to work? Are you willing to risk the side effects? And we mustn’t forget—how deep are your pockets?

After all, this book really is just a brief history of the worst ways to cure everything. No doubt, there are more “worst ways” yet to come.

Authors’ Note

This book is by no means an exhaustive encyclopedia of all treatments we now deem to be ridiculous—for that reason, you’ll notice we focus mostly on past treatments rather than current ones. Furthermore, there were many topics we would hav

e liked to cover in depth, but which we believe belong in their own book with a completely different tone, including religious-based medical quackery and the gross injustices of gay conversion therapy and racism-based treatments.

Elements

Prescriptions from the Periodic Table

1

Mercury

Of Roman Gods, Toilet Archeology, Drooling Syphilitics, an Immortal Wannabe, and Erroneous Snakes

The baby’s hands and feet had become icy, swollen, and red. The flesh was splitting off, resembling blanched tomatoes whose skins peeled back from the fruit. She had lost weight, cried petulantly, and clawed at herself from the intense itching, tearing the raw skin open. Sometimes her fever reached 102 degrees.

“If she was an adult,” her mother had noted, “she would have been considered to be insane, sitting up in her cot, banging her head with her hands, tearing out her hair, screaming, and viciously scratching anyone who came near.”

Later on, her condition would be called acrodynia, or painful tips, named so for the sufferer’s aching hands and feet. But in 1921, they called the baby’s affliction Pink’s Disease, and they were seeing more and more cases every year. For a while, physicians struggled to determine the etiology. It was blamed on arsenic, ergot, allergies, and viruses. But by the 1950s, the wealth of cases pointed to one common ingredient ingested by the sick kids—calomel.

Parents, hoping to ease the teething pain of their infants, rubbed one of many available calomel-containing teething powders into their babies’ sore gums. Very popular at the time: Dr. Moffett’s Teethina Powder, which also boasted that it “Strengthens the Child … Relieves the Bowel Troubles of Children of ANY AGE,” and could, temptingly, “Make baby fat as a pig.”

We, too, are freaked out by the baby-pig hybrid monster.

Spelling is everything if you’re going to poison your kids correctly.

Beyond the creepy promise of Hansel and Gretel–esque results, there was something else sinister lurking within calomel: mercury. For hundreds of years, mercury-containing products claimed to heal a varied and strangely unrelated host of ailments. Melancholy, constipation, syphilis, influenza, parasites—you name it, and someone swore that mercury could fix it.

Mercury was used ubiquitously for centuries, at all levels of society, in its liquid form (quicksilver) or as a salt. Calomel—also known as mercurous chloride—fell into the latter category and was used by some of the most illustrious personages in history, including Napoleon Bonaparte, Edgar Allan Poe, Andrew Jackson, and Louisa May Alcott. Why? That’s a longer story.

Calomel: Purging It All Away

Drawing from the Greek words for good and black (named so for its habit of turning black in the presence of ammonia), calomel was the medicine from the sixteenth to the early twentieth century. Despite what it sounds like, calomel is nothing like caramel, though it sometimes carried the stomach-churning monikers “worm candy” and “worm chocolate” for treating parasites. By itself, calomel seems fairly innocuous—an odorless white powder. But don’t be fooled: It’s as harmless as your khaki-clad next-door neighbor who hides a basementful of bone saws. Taken orally, calomel is a potent cathartic, which is a sophisticated way of saying it will violently empty out your guts into the toilet. Constipation had long been associated with sickness, so opening the rectal gates of hell was a sign of righting the wrongs.

“Dose: One tablet repeated” (until all hell breaks loose in your toilet).

Some believe the “black” part of its name evolved from the dark stools ejected, which were mistaken for purged bile. Allowing bile to “flow freely” was in harmony with keeping the body balanced and the humors happy, a theory that harkened back to the time of Hippocrates and Galen. And if the insides of the bowels were dark and slimy, wasn’t it better to rid the body of such toxins?

The “purging” occurred elsewhere, too—in the form of massive amounts of unattractive drooling, a symptom of mercury toxicity. A calomel consumer could give a rabid dog a run for its money. If the bad stuff was expelled via copious salivation, that was good, right? In the sixteenth century, Paracelsus believed that “effective” (i.e., toxic) doses of mercury were achieved when at least three pints of saliva were produced. That’s a helluva lot of spit. And so, at a time when overflowing privies and gallons of loogie were the answer to a multitude of ailments, physicians found their drug of choice in calomel.

Benjamin Rush was one such physician. A founding father who signed the Declaration of Independence, Dr. Rush advocated for women’s education and the abolition of slavery. He pioneered the humane treatment of psychiatric patients, but unfortunately thought that mental illness was best treated with a dose of calomel. He suggested this for the treatment of hypochondria:

Mercury acts in this disease, 1, by abstracting morbid excitement from the brain to the mouth. 2, by removing visceral obstructions. And, 3, by changing the cause of our patient’s complaints and fixing them wholly upon his sore mouth. The salivation will do still more service if it excite some degree of resentment against the patient’s physician or friends.

Resentment against your doctor and BFF is a fantastic side effect! But in truth, Rush was replacing hypochondria with heavy metal toxicity. Another side effect was mercurial erethism, a neurological disorder that includes depression, anxiety, pathological shyness, and frequent sighing. Together with tremors of the limbs, these symptoms were often called mad hatter’s disease or hatter’s shakes (for the hat-making workers who used mercury in the felting process). In addition, toxic patients could suffer from lost teeth, rotting jaw bones, and gangrenous cheeks that produced facial holes, exposing ulcerated tongues and gums. Okay, so what if success meant that Rush’s patients turned into extremely moody Walking Dead extras?

Benjamin Rush, founding father, wants you to poop excessively.

When the mosquito-borne Yellow Fever virus hit Philadelphia in 1793, Dr. Rush became a passionate advocate of extreme amounts of calomel and bloodletting (“heroic depletion therapy”). Sometimes, ten times the usual calomel dose was employed. Even the purge-loving medical establishment found this excessive. Members of the Philadelphia College of Physicians called his methods “murderous” and “fit for a horse.” Earlier, in 1788, author William Cobbett had labeled Rush a “potent quack.”

At the time, Thomas Jefferson estimated the Yellow Fever fatality rate at 33 percent. Later, in 1960, the fatality rate of Rush’s patients was found to be 46 percent. Not exactly an improvement on the status quo.

Ultimately, it was Dr. Rush’s influence on improving Philadelphia’s standing water problem and sanitation—plus a good, mosquito-killing first frost of autumn—that ended the epidemic. Alexander Hamilton, a friend of Dr. Rush, had become ill himself, but turned to another doctor who employed gentler methods. “In his theory of bleeding and mercury,” Hamilton wrote, “I was ever opposed to my friend … whom I greatly loved; but who had done much harm, in the sincerest persuasion that he was preserving life.” Hamilton survived, but Dr. Rush’s reputation didn’t. By the turn of the century, his medical practice dwindled to nothing.

Still, calomel continued to be used. It wasn’t until the mid-twentieth century that mercury compounds finally fell out of favor, thanks to a solid understanding that heavy metal toxicity was actually, you know, bad.

Quicksilver: A Beastly Beauty

Most people know of elemental mercury as that slippery, silvery liquid once used with ubiquity in glass thermometers. If you were a child before helicopter parenting or organic anything, you might have had the opportunity to play with the contents of a broken thermometer. The glimmering balls skittered everywhere and delighted children for hours.

There was always something mystical about “quicksilver,” as it was often called. Its older Latin name, hydrargyrum, spoke to its astonishing uniqueness—“water silver”—and gave rise to its Hg abbreviation on the periodic table of elements. The only metal that is liquid at room temperature, it’s also the only element

whose common name was taken from its association with alchemy and a Roman god.

So it almost makes sense that people expected magical things from mercury. Qin Shi Huang, First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty (246–221 bce), was one of them. Desperate for the secret to immortality, he sent out search parties to find the answer, but they were doomed to fail. Instead, his own alchemists concocted mercury medicines, thinking that the shining liquid was the key.

He died at the tender age of forty-nine from mercury poisoning. But hey, why stop there? In an attempt to rule in the afterlife, Qin had himself buried in an underground mausoleum so grand that ancient writers described it flowing with rivers of mercury, its ceiling decorated with jeweled constellations. It’s also reportedly booby-trapped, Indiana Jones–style, with arrows that fire when disturbed. Happily for him and chillingly for everyone else, Qin made sure his concubines and tomb designers were buried alive right along with him. Brrr. Thus far, the tomb is unexcavated due to the toxic levels of mercury that threaten to release if it’s opened.

Abraham Lincoln, pre-beard, pre-hat, and not yet mercury-free.

Quite a bit later, when Abraham Lincoln was immortalizing himself in history, he too was a victim of liquid mercury. Before his presidency, Lincoln suffered from mood swings, headaches, and constipation. In the 1850s, an aide noted, “[W]hen he hed no passages he alwys had a sick headache—Took Blue pills—blue Mass.” These “sick headaches” were also known as “bilious headaches” and could conceivably be cured by a good cathartic that also “allowed” bile to flow.

So what was this mysterious “blue mass”? A peppercorn-sized pill containing pure liquid mercury, licorice root, rosewater, honey, and sugar. Because liquid mercury is poorly absorbed in the intestine, druggists gleefully exercised their repressed aggressions by repeatedly pounding the liquid beads into relative oblivion, a process called extinction. Unfortunately, this violent compounding also allowed the mercury to be more readily absorbed in vapor form within the intestine.

Like a caffeine junkie guzzling down mislabeled decaf, Lincoln only grew worse after taking the pills. There are several accounts of his volatile behavior at the time, with bouts of depression mixed with rage, as well as insomnia, tremors, and gait problems, all of which could theoretically be blamed on mercury toxicity. He, too, may have suffered from erethism.

Opium and Absinthe: A Novel

Opium and Absinthe: A Novel The Impossible Girl

The Impossible Girl Toxic

Toxic control

control Catalyst

Catalyst The November Girl

The November Girl Quackery

Quackery