- Home

- Lydia Kang

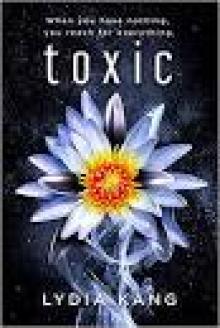

Toxic

Toxic Read online

Also by Lydia Kang

The November Girl

Table of Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Acknowledgments

About the Author

More from Entangled Teen Star-Crossed

Illusions

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2018 by Lydia Kang. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce, distribute, or transmit in any form or by any means. For information regarding subsidiary rights, please contact the Publisher.

Entangled Publishing, LLC

2614 South Timberline Road

Suite 105, PMB 159

Fort Collins, CO 80525

[email protected]

Entangled Teen is an imprint of Entangled Publishing, LLC.

Visit our website at www.entangledpublishing.com.

Edited by Kate Brauning

Cover design by Clarissa Yeo

Cover images by

seecreateimages/Shutterstock

Mr.Patichat chaikaud/Shutterstock

Interior design by Toni Kerr

ISBN: 978-1-64063-424-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-64063-423-7

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition November 2018

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Ben

Chapter One

HANA

Where is Mother?

Where is she?

Inside my room, my tiny bubble of a room, I pace like the tigers in their tiny iron enclosures from Earth’s old menageries—what did they call them in the vids? Zoological parks? Mother is never missing at breakfast. Never. And she is always here when I wake up. I have never begun my day without her warm presence, her crinkling, smiling eyes.

Where is Mother?

To make things even more worrying, I’ve been asleep for too long.

It had been one entire week that I was embedded in Cyclo’s matrix of the ship’s walls, held down by her soothing chemicals while I slept. But normally, I sleep only for forty-eight or seventy-two hours at a time. One week is far too long.

Usually, there is breakfast on the table, perhaps some rice. Usually, there is Mother, waiting for me after a long shift in her incubation labs.

But there was no breakfast waiting for me.

No Mother, for that matter.

My stomach growls, and I press my hand against my belly, willing it to be quiet, but what I want to do is quiet my mind. My thoughts are spinning, crashing, shattering with everything that is wrong. My eyes are trained on the door, hoping that it will open and she will be here and this will all be a mistake.

Please, please be a mistake. Maybe an embryo in the lab needed desperate attention for days, and she had to leave me alone for longer than usual. My stomach grumbles again, and I wring my hands, hissing at myself.

“Silence!”

It’s a familiar saying in our room. Not that anyone could hear me—the gel walls and the bony endoskeleton make it sound proof, but Mother was not born on Cyclo. She was born on Earth, where walls are made of things like trees—no, wood—and pigment—no, paint—and could readily hear conversations right through them. But maybe if I say the word again—a word that always seems to simultaneously cut and suffocate me—maybe it will bring normal back, like a prayer of wishes.

Silence.

In my thin robe, I continue to pace, my bare feet pressing against the blue gel-like matrix of the floor. It’s already been over an hour since I’ve awoken.

“Where is she?” I demand.

No answer.

Cyclo has been taught never to answer questions not directly asked of her. Otherwise, she would answer everything. When she was a young creature, before she grew into the enormity of this three-kilometer-wide diatom in space, she would answer all the questions in her color language, and it was chaos. Crew members got headaches from the nonstop, vibrant displays. So, for their benefit, each room on the ship has a color translator to help the crew.

I don’t need a translator. I understand her color language far better than the crew, and with more subtlety than the translators. I can see beyond the color spectrum that others can, thanks to Mother’s genetic tinkering with my retinal cells. So Cyclo’s nuances are only seen by me, not her. Other humans are like pigs trying to communicate with jellyfish; their interpretations are so primitive.

But, as a favor, Cyclo has learned to phonate air bubbles and actually speak to me, particularly when I’m lonely. I try again.

“Cyclo, where is Mother? Where is she?” My hands are now grabbing at my ponytail, clawing in agitation.

The matrix on the wall warps, involutes on itself, and a face appears. It’s a woman’s face, like Mother’s but different. Like an ajumma, or auntie. An ajumma made of shimmering blue glass.

“Your mother is not here,” Cyclo says in her vibrating, watery voice.

I stand there, not knowing what to do. Somewhere inside of me, a seed of doubt and fear grows steadily into a tree, strong as stone. Where could she be? I can’t call her or communicate to her—it’s strictly forbidden. After all, no one knows of my existence on the ship except for Cyclo and Mother.

Mother is the ship’s reproductive engineer, in charge of making sure the crew’s population on Cyclo stays steady and functional. New embryos are decided upon by the leaders of the ship, not the needs of a human who wishes to have their own child. Mother carefully tends these new crops of fetal crew members with a calm expectancy. And yet, I was not needed for the census, or for stability. I would be considered expendable. But she made me anyway, in secret. Kept me in secret. And when she couldn’t be here, Cyclo cared for me.

Mother was the only person required to report census data, so she could hide me. And Cyclo, who is programmed to care for all of us, had no issue with taking care of me, too. My caloric and nutrient needs were accounted for via Mother’s personal lab records, and easily hidden. There was never a reason for a random crew member to ask, “Cyclo, is there an unsanctioned, extra human aboard this ship?” So Cyclo never had to answer the question.

I stare at the membrane door. She must be busy tending to something in the labs. That has to be the reason. To search her ou

t would be to put my very existence, and my mother, in danger. After several moments, while Cyclo pulsates a gentle, light lavender on the walls (patience, waiting), I decide.

I shall wait.

So I wait another hour. It feels like a very long time. I knit some more of a little afghan I started last week. I read some Shakespeare, The Tempest. I’ll reread the story of Cyclo’s genetic creation and birth, down to the details of which percentages of her genes have been synthesized, which were knocked out, which were enriched via cisgenesis or transgenesis. I’ll read Mother’s diary, filled with stories of when I was smaller and her delight over every milestone of my childhood. I eat a precooked, synthetic yam porridge that I find in our food cupboard. My mind is whirling so fast with thoughts I don’t want to consider. The panic is there, simmering under my skin, but I cannot unravel over what I don’t know yet. So I wait.

Mother doesn’t come.

…

My heart is beating so fast I can barely stay standing. I have clawed my robe until it has holes in the edges.

It has been six hours now. I am absolutely forbidden to leave my room, a room that does not exist in the consciousness of any crew member except my mother, hidden as it is in the most unused part of Cyclo’s body, the northeast quadrant, alpha ring.

For the last two hours, I’ve raised my hand countless times, poised a few inches from the door, before dropping it. Even touching the door is strictly forbidden. But I can’t wait here for much longer. Where is Mother? Where could she be? I’d even read the last entry in her diary, looking to see if anything was off, but there was nothing but our last discussion on why hedgehogs are not related to sea urchins. My eyes are full of tears, and I’ve already cried several times out of sheer panic.

I keep my voice steady and say, “Cyclo. Please open the door.”

Cyclo, not bothering to speak because the message is too urgent, blanches with white that moves in waves over the door.

Forbidden.

“Cyclo. Please open the door,” I say again, this time my voice cracking. I’ll only just peep my head outside, just a little look. I won’t step a foot out there. I know people will be walking the hallways. But if no one is there…maybe I can make my way to her lab and see why she’s delayed. I know exactly where it is. I’ve spent much of my life studying Cyclo’s every detail—the story of her birth, the way she harvests starlight energy, the layout of the ship down to every single storage vacuole and crew member unit.

But of course, I’ve never seen any of it. Only my room. A day would come when Mother introduced me to the crew. The day was coming soon. We’d talked about it. And then I could say that I’m not just a parasite hidden on the ship, like a worm or a barnacle. I could tell them how much I know of Cyclo—I could be useful in any position they needed me. I would be worth keeping. Wouldn’t I?

So if Cyclo could only let me out of this room, I could find Mother. Her gestational labs are located due north, in the alpha ring, only about fifteen hundred feet away, counterclockwise. Cyclo, being relatively flat and circular, was assigned the familiar Earth directional vectors of north, west, south, and east since its creators were Earth-born. And as it doesn’t look like other spaceships, with an obvious way to use the traditional nautical designations—bow, stern, starboard, port side—Cyclo was mapped to feel like a huge compass within the hand of the Pleiades star cluster.

North. I need to go north.

I put my hand on the membrane. It is warm like my own skin. Cyclo acquiesces, changing her shade to a yellow with matching iridescence that shows she is worried for me, and displeased with my rule-breaking. A hole appears in the membrane, widening outward as the organic, bony edges of the door appear.

My heart is thudding so hard, I hear it in my eardrums. Cyclo can probably sense it, too—her color hasn’t normalized. She can see, taste, touch all my emotions. She is worried for me. I poke my head out of the doorway quickly, looking left and right before withdrawing. I’m hyperventilating from my brashness. The hallway—which I have never seen before in my entire life—is smooth-walled and is a wavering color of blue mixed with Cyclo’s worried yellow. The floor is very gently curved, with one door at each end. It is empty.

So I slow my breathing, and take a step into the hallway, feet bare, still in my thin robe. Surely, Mother is nearby. But what if I encounter a crew member? What will I say that won’t get us both in serious trouble? What in the stars will I do?

Hello. I’m Hana. Have you seen Dr. Um? I need to speak with her.

Let me explain myself. I know so much about the ship. About Cyclo. I can be useful, just let me explain.

I walk quickly, maybe twenty paces. Already, my legs feel wobbly taking long strides. I am only used to walking within a room ten feet in diameter. There are rounded plastrix dots every ten feet or so. They must be the translating comms. I touch the door at the far end of the hallway, open it, pop my head through again. No one. There is another corridor. And another. Every time, I expect to introduce myself to a stranger, a real human that is not my mother. My heart rate trills with anticipation at every door, slows with disappointment and dread after each one opens.

They are all empty.

A bright purple line appears on the wall, pulsating in the direction of a leftward corridor, though I know exactly where to go. Despite my anxiousness, each new step brings a tiny thrill that makes my fingertips tingle. Here are the walls I’ve only studied on my vids! And the corridors on the beautiful maps of Cyclo that look like a spinning flower with smoky, ephemeral tendrils at the edges! I’m finally outside my room. I’m finally seeing Cyclo the way she’s meant to be explored.

The purple flashes again for me. Strangely, the translating comm says nothing. Isn’t it supposed to verbalize what Cyclo is saying? I’ll have to look into why it’s not. I don’t remember that malfunction happening before I’d gone to sleep. I start running, feet padding along the squishy matrix, my robe flapping softly against my legs as an excruciating anguish begins to set in. The ship is vast, after all. It’s a quiet quadrant, but Mother always said that it wasn’t completely empty. Maybe Mother is where everyone else is.

After several more empty corridors, I enter the north quadrant alpha. I find a room full of plastrix terminals and chairs and walls of 3D computation boards, and another curved room with a long table that’s the mess hall, but devoid of food or plates. A purple line flashes to a door, and it opens into an enormous laboratory, complete with long tables, fluid-filled incubation chambers with no embryos, walls of nutrient pods, biomonitors. Everything is off, empty, blank.

Oh no. No, no. And now I’m crying.

Mother is not here.

On the right, there is a long window made of a clear, indestructible plastrix material embedded into Cyclo’s endoskeleton.

Oh!

I have never seen outside of Cyclo before, and it is so breathtaking it nearly buckles my knees. Black and enormous and glittering with stars. I run to it, letting my hand smack against the plastrix, eyes wide and searching, tears still dripping off my chin because I am so alone, and I can’t find her, and despite this breaking within me, the universe has just opened her oyster shell to me. I recognize the starshine of nearby Taygeta and Sterope, bright fists of blue light with interstellar clouds wisping around them. It’s so beautiful, and Mother isn’t here to share this with me. Every first of my life has been in her presence.

As I look out at the sparkling light in the velvety darkness, it’s obvious what I must do, but this is foreign territory—I’ve never even had to process this question in my mind.

I wipe my dripping nose and eyes with my sleeve, trying to catch my breath. “Cyclo,” I say.

Her voice comes from somewhere behind me on the wall. “Yes, Hana.”

“Where…where is the crew of the ship?”

“The crew is not here,” Cyclo answers.

Nausea fills

me. I choke out words before I can possibly vomit my porridge. “Cyclo, where did the crew go?”

“The crew has evacuated onto the seven major transports of the ship. They are currently in hyperspace, and are on their way to Atlas Station IPX-400.”

My knees buckle for real, and I drop to the soft floor. That station is very far away. As in, years away by hyperspace travel. And they cannot communicate with anyone while in hyperspace.

“Cyclo,” I choke out. “My mother. Where is she right now? When is she coming back?”

Her colors flash in pinkish sympathy. She doesn’t form a humanoid face to speak, because her colors are so much more eloquent when words are not enough, and she knows this. Ellipsoids of pink, orange, and silver pulsate with truth, sadness, and sympathy.

I read the colors with a sob.

Oh, Hana. Your mother has left the ship, forever.

Chapter Two

FENN

This trip is all about firsts.

First time away from my home planet. First interstellar travel. First spaceship job.

First time dying.

Technically, this is a list of lasts, too, if I’m going to be really nitpicky.

God. How did I end up here?

I’m sitting on the bridge of the Selkirk and glancing over the readings of our voyage so far. We should be arriving at the Calathus within the next hour or two. It’s in sight now—a bluish-white disc in space with a wispy and irregular fringe at the edges, cut with a pattern of fenestrations. It sort of looks like a snowflake and a moon jellyfish had a wicked fight, followed by makeup sex, and then ended up birthing the Calathus.

“Cyclo. There it is,” Portia says. “I mean she. She’s really a beautiful crvat, isn’t she?” Portia’s the one actually driving the Selkirk right now. I don’t know what crvat means. Probably “interstellar biosynthetic human habitation complex.” Possibly she means “jellyfish.” Learning Portia’s language is not high priority at this juncture in my life. Even though I’ve had nine months to learn on this trip so far, I’ve decided that it’s best to not always know what Portia is saying, particularly when we squabble over food. Which I’m always stealing because I like her Prinnia food better than the synthetics I usually eat.

Opium and Absinthe: A Novel

Opium and Absinthe: A Novel The Impossible Girl

The Impossible Girl Toxic

Toxic control

control Catalyst

Catalyst The November Girl

The November Girl Quackery

Quackery